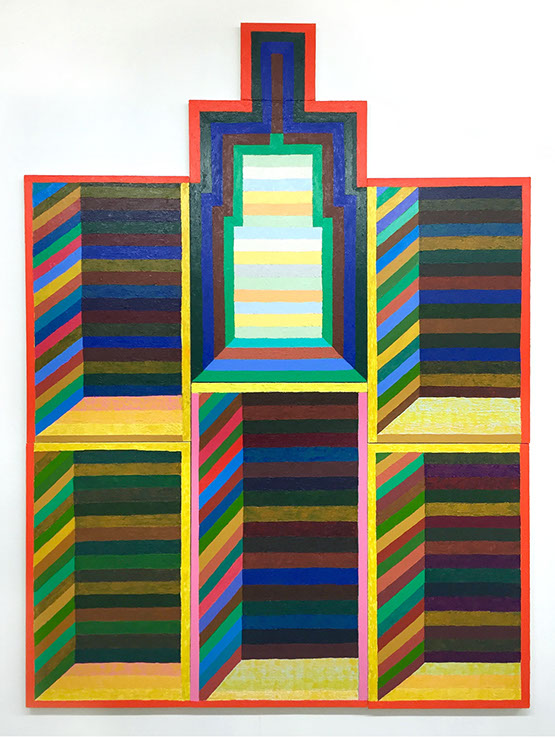

Evening Of The Yarp, 2015

58" x 47", acrylic and oil stick on canvas

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

Matt Phillips with Matt Kleberg

MP: So how do you feel living and working in NY and moving here, enrolling at Pratt for graduate school, and living and painting here for the last two years? What has that experience been like?

MK: The first painting I made at Pratt was a reboot of the stuff I was making in VA –these Texasy figurative paintings with a lot of the figures painted out and obstructed, these graphic shapes that were crashing in. And it was good but terrible. I mean it was a “good” painting, but it was kind of soulless. And I had my first crit and the professor was like, “okay this can die.”

MP: “This can be excused.”

MK: So I got it out of my system. I mean, I made two years of bad paintings. But right off the bat, I was like, “okay the old order is dead and now I get to -and have to- completely restart.” And so that is when drawing became a big thing. I mean if you came into my grad school studio, you’d think I was schizophrenic or had multiple personality disorder because every week it was like a different painter was inhabiting the space. You could lay out the work now and see a thread. I can follow it now, but at the time it was like taking shots in the dark.

MP: Good, but hard I imagine. I feel like you encounter within your peers a high degree of professionalism. I remember that... the people who already had a specific body of work that they had been developing and they were coming to grad school just to produce within that body of work –that pre-established project. And to be able to endure the public searching is a really difficult part of being in school. Or it can be.

MK: Yeah, I went from being an artist in Virginia [where] people knew me and they knew the work, to coming to NY and being completely anonymous and having no idea what my work was about. So even if I wanted to have some kind of identity it wasn’t available to me. Becoming anonymous was great. It allowed me to make a bunch of terrible work without feeling like there was something on the line –other than making the work better and letting the work kind of take over.

MP: Maybe like more permission to fail, more permission to come up empty handed in the studio.

MK: And permission to experiment and do things that didn’t make sense that I kind of knew were set to fail from the beginning. The paintings that I have kept from grad school all have little kernels, none of them are terribly successful, but they all have little kernels of stuff that I held onto along the way.

MP: So that thread that you describe, would you say that that was more of a formal thread? Maybe how you were using the color or the material, or do you feel it was more about the form or something image based that you would extract from the painting, or sort of mine from another picture –because you talked about birds, and then there was a tequila bottle.

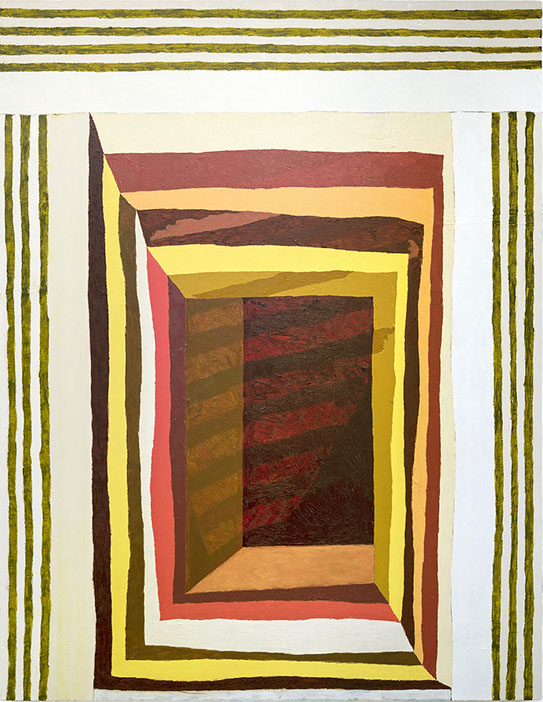

A Late Encounter, 2015

92" x 68", oil stick on canvas on seven panels

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MK: I went from having certain formal affinities in painting and applying them to “content” or “imagery”. I went from that to the form and imagery and content all becoming one-and-the-same until they are wrapped up in each other. I came in making photo-based figurative works [and] realized that the photo had to disappear. I started making paintings that were based on drawings of stylized figures. I remember making this one big narrative work of a guy on a horse with his shirt off holding these two dead vultures by the legs with a stormy sky. And there was this iconographic, apocalyptic thing, but I remember thinking, “Alright, there is a lot of things about this painting that I like, but the narrative…”. I wasn’t so interested in trying to recreate these narratives, so I found my favorite part of the painting

-which was the vulture- and I just played with the form of the wings and the legs. They were kind of craggy, geometric, stupid looking birds. One of them, I ripped the head off and I decided, “Alright, that’s the only thing in that paintings that is really totally essential.” I was pretty flustered and I thought I would make a painting that was just a bird with nothing else in the painting. So I got a big square canvas and literally jammed a bird into the canvas. And the bird looked like it had had its wings broken, like it had been jammed into a box. It went up against all edges and everything was kind of turned on over itself, but it still had this frontal, central, iconographic orientation. That bird started to break up into pieces. I broke it up into wings, and heads and legs, and those things got reorganized, and they started to pile up. This was happening mostly in drawings. It became less crucial to me that they were bird parts, and it was more about these abstract shapes that were piling up. And those piles were becoming more or less architectural. So I made a drawing of these big piles. It looked like a pile of boulders, a pile of shapes. It looked like Stonehenge. They were stacking up and becoming architectural spaces. And I kind of freaked out because I lost what I thought was so important, which was all of the “imagery”. The boulder piles were starting to look like altars, and I started putting things in the altar. I was drinking a lot of Mezcal over the summer between my first and second year and so I was making altars to Mezcal.

MP: Sounds like grad school in a nutshell.

MK: There was a Mezcal bottle one week. There was a scull the next week –or in the earlier painting, the guy with the vultures. There was always something in the central space. And now this architectural element had been erected around that space and I finally plucked out the figure, or the bottle, or whatever that thing was, so that central space became the subject. And that is when the stripes showed up too. The stripes were a way to construct the space and also a way to confuse it a little bit. It allowed the space to be busy and active and have some kind of movement while also being essentially empty.

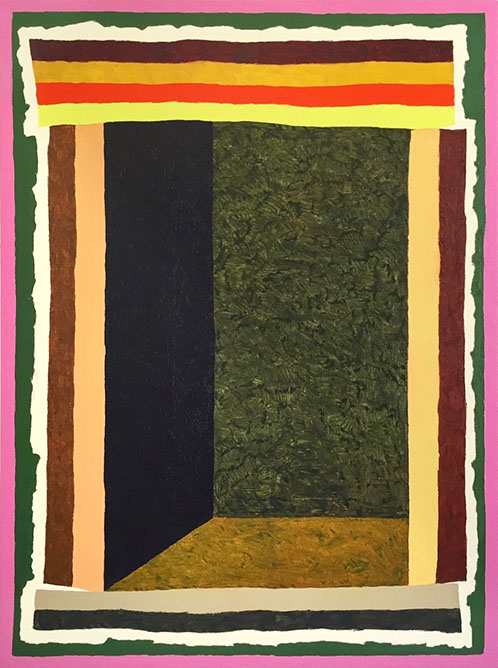

Eating Wife and Friends, 2015

60" x 48", oil stick on canvas

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MP: I’ve seen that bird painting at your Pratt studio. And I feel like there are two different narrative strategies that you are talking about. There is the sort of figure on the horse with the birds that comes with certain expectations of cinema, or the way a narrative in a painting works. But in the new body of work you’ve arrived at a sort of stage form -where this is an actual form where we’ve come to witness narrative. But in some ways the paintings are also more flat and static and about the process of making –like the duration of their making instead of the way that you would read a narrative painting by Titian. But they both have this way that we come to expect or witness a story. There is a kind of connection.

MK: I feel like in the Titian painting, you have a couple of narratives going on. Or take Caravaggio, The Musicians. You have the literal narrative, which is figures engaged in this activity, and there is cupid there so there’s some symbolism and they are playing music, and that’s the deal. And that is kind of how I thought of the guy with the vultures: what is this guy doing? And that became a little bit less important. But in The Musicians, you also have this formal narrative, like the way that he moves your eye around. You have the slope of the shoulder moving into the crook of the arm that catches the other guy’s tunic, and this is the narrative of how you experience the painting formally. And that was more exciting to me. Just like the bird parts no longer really mattering that they are bird parts, but the fact that there are these shapes that spoke to each other.

MP: It’s like the difference between what the painting is about and what the painting does to you.

MK: Yeah, “aboutness" is a word I think about all of the time. And so you talked about theatre or the stage, and with these recent paintings they go back and forth for me, feeling like a stage that has just been emptied –like it has been stripped of it’s narrative, or this anticipatory space, like this stage is set and the narrative is about to enter the stage.

MP: So like expectation?

MK: Yeah, you can apply your own narrative to it, but I like that expectation or loss.

MP: Do you feel like the paintings sometimes play with denial and disappointment? Like there is this elaborate setting of the stage, constructing this structure, and as we are moving towards the middle we are waiting for it to happen, building up expectation? And one potential reading of the painting is, this stage is empty. We come to the painting expecting to get something, but in another way the paintings are actually a place to receive. They’re empty, so you could deposit something in the painting as much as walk away with a story or form.

MK: And that is where this idea of expectation and disappointment goes back to the form. I love this idea. These paintings are like frames within frames within frames within frames. There’s a lot of framing. There are stripes. Everything is rhythmic. And some have curtains drawn back and everything is vibrating into the middle… and the thing is empty. But those empty spaces are also the only place where any kind of illusion happens. They are very flat paintings. The illusion is kind of fleeting. It always collapses, but that is what paintings forever have done. They give us these moments of magic where this flat space becomes another world. So on one hand those spaces are empty and on the other hand, that’s the only place where the painting magic happens.

MP: Right. Because one way I think about it, the stripe, the line turns into a plane. And the plane turns into a form, and through some sort of small subversion of the rule of the painting, line turns into form and light begins to happen and space begins to happen and you are sort of tapped into that spark.

MK: I love that.

MP: I love that too.

Knowing He Was Not My Kind, 70" x 54", oil and oil stick on canvas, 2015

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MK: I definitely feel like these paintings have an element of loss or disappointment.

MP: It’s countered by discovery though, right?

MK: Yeah, and I am interested in those moments where that space, or that volume, or that light shows up and then it disappears… or that space recedes and then it snaps back. There is discovery and there is potential. It’s not just rote disappointment.

MP: And it’s getting to have it both ways. It’s trying to heighten contradiction.

MK: Yeah, I love that. That’s the dialectic. Saying it’s there and it’s not there, and being able to say yes to both those things. I like the paradox, the oxymoron, it being contradictory because that feels like human experience.

MP: So if you are making a painting that is about contradiction, how do you resolve a painting that is trying to do two opposite things? Is that what is going to bring you back to the studio on the day to day? Do you feel like there is a point where that conundrum becomes apparent and you get interested in it? Flesh that out for me if you can.

MK: There is that moment in making the painting where that contradiction starts to present itself and I get really excited. I will put down a plane that begins to push a space back, and then I’ll bring in a color that tugs that space back out, and then I will put something down that pushes it back in. There is this tug of war and with every painting that is just really exciting to me –the checks and balances and trying to find a place where there is tension.

MP: With color for example, there is a kind of duality or tension in the way that the color works in a picture. In one read, or in certain moments in the painting, it feels like it is very much about rhythm, and time, and structure, and in another moment it feels very much about space and light. Do you think about those two things as being in conversation or tension in your paintings?

MK: Yeah, all the time.

MP: What about the color melody that happens in each picture? How does color evolve in your paintings? Is it something that you sort of figure out in a palette prior to the painting, or is there a lot of improvising, and adjusting, and developing directly on the canvas?

MK: So far there are two ways that I’ve been working. They oscillate back and forth. [In] the first stripe paintings, the color palette was totally scatter shot. I would put down a stripe and then I would have an immediate feeling of, “You know what would be really beautiful next to that? It’s this.” And then I would kind of suppress that thought and think, “you know what would be really terrible with that? It’s this.” And I’d put down something that shouldn’t work. And then I put down something else. And I’m just reacting to each move with the goal of trying to make something awkward on the individual level work as a whole. In those, the color is a lot of checking and balancing and striving for a certain off-ness. And then I’ll swing back and do a green, yellow and white painting. I’ll try to make a painting with a more limited palette work.

MP: It seems like there are certain structural things that you are exploring from painting to painting. Like the bones of the picture remain relatively fixed, so then it becomes about a certain kind of color chord or a certain kind of generative light that you are exploring from picture to picture. Does that feel true? Would you say that within this there is a thread of studying light from painting to painting, or space?

MK: For the most part, like you said, they are similar. It kind of gives me an excuse to see what purple, pink and green can do together. Or see what yellow, green, white and brown can do together, and let that be the variable. Take the structure as more of a given and then investigate how those different colors might work together. [Or] the structure changes but some of the colors stay the same. [For example], a lot of these paintings have ceilings, and I wanted to see what would happen if it didn’t have a ceiling; if the whole painting would fizzle out at the top, or if you could still bounce the eye around it.

MP: Well, it’s a very different kind of way of implying the body in relation to this, whether you could pass though the picture or be held and contained within the picture. They just totally have a different kind of architecture at play.

MK: You mentioned the body and that is something that I think about all of the time. If these were figurative paintings with the figures plucked out, now I see the body showing up in the treatment of the line. Letting the hand show through in the line. But also in these niches, I am thinking about head sized spaces, and torso sized spaces, and figure sized spaces that you project yourself into.

MP: So in a few pieces in your thesis show you sort of stepped outside of the traditional rectangle support with an illusionist image that it contained, and you actually started to use and incorporate true building materials like wood, and brick and multiple panels, and you really started to reference altars and polyptychs that I think of like from 14th century Italian painting. How do you see that kind of offshoot of the project, does that feel like something that you just had to do it to see it, or do you feel like it is still up for grabs right now? What kind of issue do you feel like you could explore, only though pushing them towards sculpture and architecture that you couldn’t do in a traditional painting language?

MK: As the paintings were getting more architectural themselves, I felt like there was space to build and construct. So there were a few paintings where I hit a roadblock. And for the first time, instead of reworking that space within the rectangle, it made sense to add on and build out. I was looking at altarpieces and those silhouettes as a way to embrace the architectural. If we are talking about all of this anticipation towards the center where the space is ultimately empty. I like the idea that if the figure was not present, the painting at least made itself present. So the sculptural elements for me are the painting coming out to meet. It is inhabiting the same space that you are. Paintings are always physical things, they always have a physical presence. The traditional view of the rectangle is as a virtual space where entire universes are created. The sculptural elements were a way to heighten the idea of paintings’ actual “thingness”. It’s another body in the room. It’s like a thing that you could drink a cocktail with and have a conversation with. It gives and receives. I feel like that happens with our favorite paintings anyway. With these being empty paintings, I like that idea of these empty paintings reaching out and just coming out in the room with you.

Do What Say Do, 2015

59" x 44", oil stick on canvas

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MP: So like an active, palpable emptiness. Have we talked much about the reference to the altar and the polyptych? Is there more you want to say about where that reference came from?

MK: On one level it relates to the theatre or the stage. I can say it on a theoretical level and a personal level. On one hand it acts as a stage. It is a framing device. They frame a space where action is supposed to happen. They frame aura. In an altar’s case, you are blessing sacraments. On the stage, actors are lifting up language and emotion –something mysterious. And in both cases it is all about the creation of aura. I like that idea of framed action. That is kind of what paintings are too. The rectangle is a frame. It says here is where the mystery is; here is where the action is. Of course that becomes different when minimalist sculptors take pieces off the wall and onto the floor. All of a sudden we become actors, but that is playing off the idea that this artwork on the wall is a stage where something happens. On a personal level, I grew up in Episcopal churches. There was a season in college where I thought I was going to go into seminary. I studied theology. I was always the student really digging into the all of the contradictions and paradoxes that come with any kind of belief system, and I really wanted to parse out the contradictions, smooth them out, make them go away, and then understand the core. And as I have gotten older, I have realized that doubt plays a huge role in my own spiritual understanding, and that has become a really important thing. Disbelief or unbelief as a really important part of belief

–and the embrace of the mystery, and embrace of a contradiction. That is why it is really important to me in these paintings that the space is there, the space is not there.

MK: Yeah, and that falls in the same category as the stripes and the color and a sense of rhythm. There is that activity that says there is something there even though they are kind of futile spaces.

MP: Well, it’s funny though because one of the things that I respond to in the pictures is, in a way you could say that they are empty. But in another way you could say they are very much about the natural world –about motion and change. And I feel like one of the things that you do is that you come up with a repetitive structure. And then within that structure we experience change -usually within your color decisions whether it is value or hue- and I always think about, like in painting, the way that we get to describe motion. It is about things that are changing within a regular system.

MK: Like the aberration. Yeah. In the stripes, it is always interesting to me to build up a system of predictability. These colors are working together, and then throw a wrench into the whole system. That is where you turn or pivot and it produces a kind of action or motion.

MP: It produces a time based reading and not just a spatial reading of the picture. Where you get to witness the change within that static structure. Someone like Bridget Riley, her whole project is about that; things changing within a predictable structure. I think about Riley and her relationship to stripes way before I think about Frank Stella and his idea about stripes –not that it is either/or.

MK: How do you see the temporal quality of Riley different from Stella?

MP: In particular I am thinking about the black paintings. Where it is always a black mark of the same width, same brush, same paint and it is really emphasizing flatness in the static object, and the here and the now and “my hand across this”. And in a way, I think Bridget Riley takes that and then starts to subvert it where things change. Colors change through that system, so it starts to become about space, and undulation, and rhythm, and heartbeat, and wind, and the waves, and you feel them sort of evolving through a structure –like the way as if you were to watch a movie it is like all of these frames are a consistent given, but within each frame you have an evolving image. So for you, that would be color decisions evolving through the frames.

MK: So that seems like what you are talking about as the natural world; the natural world into the painting.

MP: Maybe natural energies.

MK: I think Bridget Riley is more generously explicit with that kind of reference to a natural energy. I actually think that Stella would say that it is all there in his too, but I think his withhold a little bit. He actually talks about embracing the pictorial space of Caravaggio in his stripe paintings. And so the interval, the change of direction, for him, those would be that illusionistic, natural, outside world being let in. But they are only just so, whereas Riley is more explicitly generous. She gives it to you, like the wave or the air coming off of that painting.

MP: I think of those early Stella paintings as also being incredibly emotional paintings actually. And I think that he sometimes intentionally denied; oh it is just a painting, what you see is what you see, a stripe is a stripe… but they seem to be very much responding to the holocaust and WWII.

MK: And you can get that even the way he titles his series; he names a painting after a species of bird and you can’t help but project that into the work. A lot more seeped in than he admits.

Drawings in the studio of Matt Kleberg, 2015

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MP: Talk to me about the drawings. You draw a lot. Some of these seem like they are totally just invented in the sketchbook. Some feel like they are specific studies of Giotto, Cimabue, maybe a Fra Angelico. Tell me about how you see those. How do they serve as a tool for the paintings? Are they complete pieces unto themselves?

MK: I think of the drawings as an independent thing. Sometimes if a drawing really sticks with me, or if a certain form or structure really sticks with me, it will find its way into a painting and so becomes a sort of study. If a drawing becomes a study, it is usually black and white so that the color investigation can still happen fresh on the canvas. But I draw all of the time. It can come from seeing a piece of art; Fra Angelico for sure. I go to the MET, bring a sketchpad, and spend hours in the Byzantine section, or walking around NY and seeing building facades garages, those sorts of things. The way I draw is scratchy and repetitive, and I like that repetition. Like scratching away obsessively or idiotically in a small part and then doing it again and doing it again and then stepping back and perceiving the whole.

MP: I feel like that is something that is important to know about the paintings. These aren’t quick stripes. These are you really inching your way across the surface by hand. And that sort of touch and tactility and controlling the speed in which the eye reads a lineal element feels really important when you are face to face with the pictures. I guess I assumed that that was something you discovered through drawings that you didn’t try to have the paintings retain that quality.

MK: For sure. I’ve started using oil sticks mostly, and that was a way to recreate that scratch drawing quality in paint. Things can get naturally wonky and you don’t have to fake it.

MP: They also don’t have the same sort of air as the drawing. Something about density and the weave of the mark in the drawing, that it feels like you have to achieve that through color when you get to the painting stage.

MK: Which is why I still mostly draw in black and white. The drawings usually get ahead of the paintings, and I don’t want the paintings to be perpetually dependent on the drawings. I like to bring as much of that into the paintings, but the color is a way to let the paintings be their own thing, and have their own ways of succeeding and failing, and not just become the illustrations of the drawings.

MP: It is also interesting because on one hand I feel like the paintings extend the tradition or the form of the altar, or the polyptych, but they also feel very contemporary in terms of the screen and the pixel and this contemporary digital world that we live in. But it is funny because I always think of the digital; the images that we see now have no direct contact with the body. Do you think of that set of references? Re-inserting the body into that contemporary context…

MK: They are definitely in support of embodiment. I will take the pixel reference because I do feel the way the tiny mark creates the whole. I watch a ton of movies, but I was the kid who didn’t have a game system and whose friends would invite over to beat my ass at Golden-eye. Invite me over and then kill me a thousand times. I mostly grew up outside, not inundated with the digital. But I am still a product of the 80’s and 90’s, so it is still there.

You were making work that was referencing or responding to altarpieces and that kind of sacred object when you were in grad school, right? What was your relationship to that? Was that an art-historical endeavor?

MP: I think for me it was probably like you, I was just looking at that work. I was really obsessed with 14th cent Italian painting and I just liked that it was this given. It was this physical form. It allowed the painting to be both image and object and I’ve always been really fascinated by that truth. It was just the starting point where I could push my pictures towards a sculptural direction and just rely on that traditional given form, and start to see what I could bring to it now.

MK: It seems a little bit like Guston’s “freedom within parameters” thing where for the guys painting these altar pieces in the 1400’s or 1500’s. It was like “your givens are the triptych” and even down to “you have been commissioned to do a deposition, or an annunciation, or a crucifixion”, but then within that you all of a sudden have all sorts of freedom. And you can go wild in that space.

MP: It’s like listening to bands doing covers of the same song. One of the other things I like about those altars is that there is a utilitarian function. They are tools. They have use, like things were laid in front of them. They were used for devotional purposes and ceremonial purpose. There is always this desire to have a painting have a clear purpose. I think that was always something that attracted me to that sort of form.

MK: I think that relates back to the architecture question; this aesthetic, theoretical endeavor that can’t get away from the body and the real world. It has to serve the world.

Drawings in the studio of Matt Kleberg, 2015

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

MP: I really love the experience of looking at the more sculpture pieces. You are contending with the object in this one to one read, but the illusionistic space is either supporting or denying that read. There is a threshold that you create where once the eye goes into the space of the picture, you are asked to leave the body. And there is that weird dissonance between size and scale kind of like hiking and reading a map. It becomes this strange indeterminacy. And I think that body, spirit, light, space, empty, full, and a lot of these kind of themes, really start to get activated in an interesting way.

There seems to be something important that you’ve kept mentioning along the way: the dissonance, the awkwardness.

MK: I think that is part of these more or less architectural paintings still having a human element. There is still this sense that the architecture or the structure isn’t air tight. In the same way that the space recedes and snaps back, the whole painting might fall apart. I want there to be a risk –a true potential for it to not work.

MP: That’s funny, because that is something that I think about in my own painting. You sort of want to assert that human touch, and that sort of imperfect edge, and that trembling hand. But then there is also that risk of it being a veneer of it, and not actually being a true mistake, or a true kind of wobble, but it is sort of like the affect. And I am curious if the longer you do this, if you start to... how your criteria around awkward has evolved.

MK: That is such a good question. I had a critique with John O’Conner -he was my Thesis advisor at Pratt- and I was really proud of one painting. It had this slab thing at the bottom and it was like a floating tabletop shape. And it was, you know, wonky and awkward and outsidery, and he just told me straight out that he didn’t trust it. That it was an art move. It was put on. And he was totally right. And so I am always questioning my own motives, and if it feels put-on, I have to reject it. When you are dealing with the trembling hand or wonky line, you always run that risk of putting-on. It is too easily likable. It’s an easy win. But I think that is where a larger scale helps –where there is room for the hand to do what the hand does. Where a straight line is never actually straight. It is harder for me to make smaller paintings for that reason. But as far as my criteria, it is about questioning my own intentions, and if I feel like I am faking it… I know if I am faking it or not.

I’ve been looking a lot lately at Beckman. And in a lot of his triptych paintings, the ground

-the way he treats perspective and space, the ground plane- always looks like it is like a Cezanne bowl of apples table-top. It is always like catapulted up and flattening out, but at the same time spilling the contents of the painting out of the painting. And I’m realizing that is why the niches are always at this angle that you are looking slightly from above so you see the bottom plane, because I like that spillage, that dump truck, dumping the space out on the viewer.

MP: Yeah, my physical relationship to the image is in question. Where I am not necessarily feet on the floor looking in, but I could also be hovering above looking down, or both. I like that idea of the Beckman, starting to challenge the membrane of the picture plane, right? Like the drama of his world are about to literally kind of fall through the picture.

MK: And it goes back to -we’ve mentioned Caravaggio- but it goes back to the bare feet of someone kneeling on the ground coming right out at you, only with the freedom of Modernism he’s able to take that space with a crowbar and really exaggerate that spillage. And it is also not so unlike pre-renaissance perspective, trying to figure out “how do I make this chair look like it is in real space?” “Well, let’s just hike up the back and drop the front.” And it looks like it has been made with two legs that are shorter than the others. We can use that device to our advantage now.

MP: What about that kind of relationship to American craft and quilts? Is that something that you think about often? The decorative arts? You mentioned a few times being sort of leery of the decorative.

MK: I think I am over the fear of the decorative, because I just like it. I like things like Gees Bends quilts, but I can’t say they are a huge direct influence. But sure, textiles seep into my brain plenty. You find pattern decoration in a lot of like early American art and folk art. And you find it in church architecture and in advertising and package design; it is kind of all over the place. NY architecture, you walk around in the old buildings and the wrought iron will have some kind of repeating pattern or the top the building will have some kind of turret –a beautiful thing.

I think that discussion of doubt: that is where I locate myself in the paintings a lot of times. I will say, I don’t think it is so apparent in the work, but I read a lot of fiction. I love Southern Gothic. Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Barry Hannah, Larry Brown. [Change in the characters] happens in these really violent, perverse ways. I think I have an affinity to that dark, jarring event. Something that on the face of it is destructive, but ultimately the catalyst for change.

MP: Like an awaking.

MK: It gives a certain clarity. And it’s not so explicit in these paintings. Although, from my perspective, knowing the history of the work being figurative paintings, I like to think of that plucking or extraction of the figure as a violent carving out.

Love Too Long, 2015

60" x 32", oil stick on canvas with artist frame

photo: courtesy Matt Kleberg

Matt Kleberg is featured in a solo exhibition titled "Coming Close" through January 8th at the New City Arts Welcome Gallery in Charlottesville, VA. He has recently been included in shows at Cindy Rucker Gallery, the Wythe Hotel, Honey Ramka, and Muhlerin. His work was included in Muhlerin Gallery's booth in the 2015 Untitled art fair in Miami. He graduated with an MFA from Pratt Institute in May 2015 and was awarded a residency at Vermont Studio Center in October 2015. Matt Kleberg lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

Matt Phillips has shown extensively in New York City and Nationally including exhibitions at Steven Harvey Projects, Brian Morris Gallery, Life on Mars and TSA Gallery. He was interviewed for Gorky's Granddaughter in November 2013. Matt Phillips holds an MFA in painting from Boston University. He lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.