The end is far (for the titans of soft rock)

Mixed media on paper, 10" x 9", 2015

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

Melissa Staiger with

Mark Joshua Epstein

This interview is a collaboration between Melissa Staiger Interviews and Painting Is Dead

Click here for Melissa Staiger's corresponding video interview.

Melissa Staiger: So I’m here with Mark Joshua Epstein in his studio. And I’m Melissa Staiger. And I’m really happy to be here.

Mark Joshua Epstein: Me too!

MS: I feel like you’re my long lost friend I just found, so I’m very excited about that, especially with all the color that you use. I feel very connected in that way to your work. When I saw your work I immediately thought of Ruth Root’s recent show at Andrew Kreps.

MJE: I saw it. I had never heard of her before. And I went. I almost cried at the show. I had to take a moment in there. I actually have the card from that show in my tote bag all day, every day. Where did she come from? Did you know anything about her?

MS: I knew her work, but from a different series. Something about the forms she presented at Kreps connected with me more. I liked the work that I had seen before, but the patterning really blew my mind.

MJE: If I have this correct, she is designing the fabrics and having them printed.

MS: Yeah.

MJE: That was mind blowing for me because that’s something I never would have thought to do. I’ve thought for a long time about physically making supports out of some of the textiles I have collected while traveling, but I feel a little weird about that. The fact that Ruth Root is printing her own fabric is a bridge between found and homemade. It might provide a clue for me for a way forward. Her show, the scale of them… ! There’s such a stereotype that works using fabric are going to be tiny. And they’re huge! Oh my God that show. And even the fact that she uses plexiglass in a such a genius way... Before we started the interview, we were talking about the heaviness of the wooden panels that I sometimes, and her show felt so so light.

And then Isa Genskin also had a show in Chelsea recently. She had this set of two paintings that were on black plexiglass. They just had holes drilled in them with grommets and they were hung with on the wall. And the plexiglass was just the support for the paint. I don’t know if this happens to you, but sometimes for me, I think about a material for years. And then it sort of gets somehow into the work. So I bought a few pieces of plexi and it’s just in the studio. One of the pieces is pink -the way a bowling ball is pink- and the other one is sparkly. I feel like one day I’ll figure out what to do with them.

MS: I can’t wait to see that. (laughter)

MJE: Circling back to Ruth Root -what gave me such life about that show was, here’s this artist I hadn’t heard of, who had just been doing her thing for a while and then that show was such a moment. Seriously, everybody was talking about that show. I loved it. I wish I’d seen it again.

MS: I know. Me too. It seems so much easier at this point in time to get images printed on textiles. I have seen websites where you can get tennis shoes with whatever pattern you wanted printed -or bedspreads even. I have been told -because I work in pattern- that “this could be a textile”. I’m not thinking of it in a textile world because somehow it feels like it would devalue it. But Ruth Root doesn’t have that problem!

MJE: I wonder if the boundaries have blurred a little bit. I think about textile design as something I would like someone to ask me to do one day -someone who already knows how to do it- and I could just come do the fun part. I spent last year in Mexico City and a big part of the inspiration for me there was textile work. I was able to spend some time in Chiapas and these women who worked at weaving cooperatives… Just the work that goes into those piece is incredible. I think those works should be considered in the context of fine arts. When someone says to you “I could see that in a

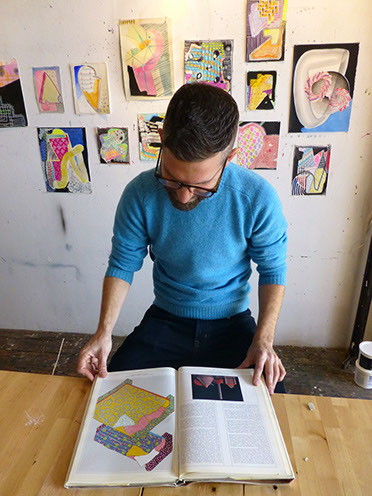

Mark Joshua Epstein in studio, November 2015

photo courtesy of Melissa Staiger

textile”, we think devaluing. I think the art world is giving us that devaluing. But maybe that’s shifting a little bit. I just saw a show at Elizabeth Dee gallery that was work by Mark Barrow and Sarah Parke. Those pieces are engaged with textiles and weaving in such a fruitful way. I think a lot about people like Annie Albers, who did incredible weavings. There’s an artist named Noah Eshkol -who was a choreographer and had a dance troupe- and with her dancers made these huge fabric collages that were incredible and underappreciated.

MS: That’s amazing. I’m going to look her up later. You mentioned being in Mexico City. To give the readers a visual -I’m sitting in front of Mark and he has a blue sweater on and it matches his eyes- behind him are these beautiful works on paper highlighted by this. Some of them were started in Mexico, some are from here. Can you you talk a little bit about that process?

MJE: Sure. I didn’t want to go to Mexico. I went because sometimes romantic relationships make us geographically relocate ourselves. So I went to Mexico City slightly kicking and screaming. When I got there though it was immediately great. I was looking for studio space and was initially frustrated for about ten minutes because there aren’t big blocks of studio spaces there, so I contacted this collective called Feral and they invited me in for a meeting. They’re a collective of artists who really concentrated on drawing. They have a space in the Centro Historico -which is a small gallery combined with a studio space. I went in and we talked about drawing and they generously invited me to hang out and make work in their space for a couple of months. So I didn’t end up needing a studio space right away. Since “Feral” is an intimate space, I started working small and on paper, and that eventually developed into a large wall frieze.

Wall Frieze at Feral Art Collective in Mexico City, 2014

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

MS: Well, you’re kind of a world traveler. You also spent time in London. Was that where you went to school?

MJE: I went to graduate school in London and I don’t know why honestly. I went to undergrad at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which is attached to Tufts University. It’s a very small school. There was no foundation year. There were no requirements. It was a super special place.

I applied to graduate schools in the states and in London. It was kind of an impulse. I got into a school that I thought would be more suited to me in London. Off I went (laughter). It was really transformative, but not in the ways that I anticipated. It was very, very hard. I was at the Slade School of Fine Art. And it runs like atelier system. You get there and you get your studio space and someone tells you who your tutor is, and that’s it. You’re sort of on your own.

There wasn’t a syllabus. I made my own syllabus -to have reading material- and I wasn’t experienced enough in the world to ask for the things I needed. In one sense, they just treated you like an artist. You were an artist to them. But in another sense, I didn’t know how to invite professors into my studio. I just didn’t know how it worked. The painting department was led by this amazing, charismatic character named Bruce McLean -who’s quite well known in the UK as a performance artist, painter and printmaker. He’s a great person, but you couldn’t work small or he wouldn’t pay attention to you. So I started making twelve and fifteen foot paintings on wood panels just so Bruce would see them as he walked by.

The ethos in London art schools was very different. With them treating us like we were artists, no one ever questioned why you did something. People felt like if you did it, it was worth discussing. It wasn’t a justification culture.

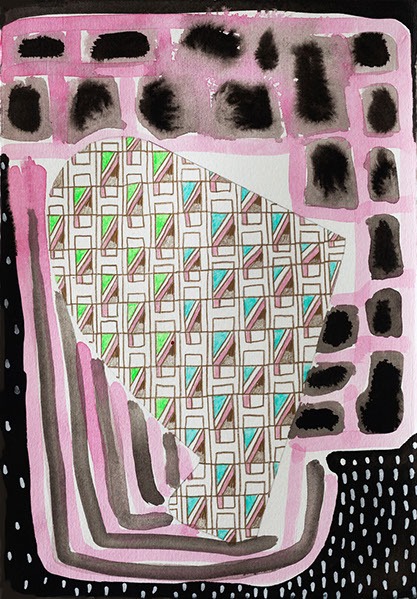

Two of hearts (I need you I need you)

Mixed media on paper, 9"x7", 2015

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

MS: I’m going to jump from that to an article you read last night that I have not read, but that I think it important to talk about, especially with my love of color and definitely your love of color in your paintings. Can you talk more about it?

MJE: Hyperallergic posted an article last night by Abe Ahn about this show Surface of Color, that is in LA at the Pit. The show and the review were about this idea that queerness can be investigated through abstraction -which is something that I think about. There are a lot of abstract painters in New York and I’ve long tried to figure out how to situate myself. I did this thing one year where I gathered as many artist statements from abstract painters as I could find, and compared them all. They were remarkably similar! They were all talking about light, and color, and form, and shape, and distilling this world around us. And I felt like for me -even though all of those elements are important- that’s not how I want to contextualize the work exactly. Because for me, the work really comes from a pretty gay place. Even if that doesn’t necessarily read in the work, even if they just look like abstractions, and even if they don’t look like there is content in them, I think queerness comes in the way I move my body and the way I hold myself in the world. So it comes into the work--maybe even just through my point of view.

What I like about this idea of abstraction as a kind of queer vehicle or queer expression is… I think abstraction is, by nature, fragmented. There’s something about challenging the supposed universality of abstract painting as well as the history of abstract painting as a kind of cis-male-straight thing, and also challenging the notion of queerness. As in, this isn’t one thing, this is 1000 things.

Reading the article last night was fortuitous because I’d just come from the opening of the Frank Stella show at the Whitney. Frank Stella is a hero of mine, but it was a very interesting counter point. Frank Stella makes all of these huge works. I think other people would use the terms aggressive and bombastic, but I’m going to use the word confident. I was really thinking about where his work fits into the my chosen lineage of painters. Coming home and reading this article on Hyperallergic which is talking about other abstract artists living now, who maybe I feel slightly more in line with in the present moment, who have taken the history of abstraction and transformed it or are transforming it, was really empowering.

I will say as a side note, that Frank Stella show had... we’ll call it the Ruth Root effect on me, where I almost wept. Just to see all that work, and to see that Frank Stella went from making these very geometric things to then making these incredibly ungeometric things, and that parts of the art world abandoned him for years... When you walk into the show at the Whitney, what’s on the first wall is one of those very geometric things from 1974, and then a crazy huge, colorful, insane painting from 1999 called Earthquake in Chili. You get off the elevator and it’s like “Yes! This is the same artist”. This is the trajectory of a career. It’s ok to do a little of this, and then a little this. Maybe the second thing you do makes it look like you didn’t believe in the first thing you do. But that’s ok also.

Going back for a moment, there are so many abstract artists who I look at who are talking either explicitly about queerness, or they are so open with how they identify that you know it’s got to be in the work somewhere. I just saw an incredible show by Laurel Sparks at Kate Werble Gallery that at least for me, spoke in these kinds of terms.

MS: I think it’s important because when things are documented and a history is paved, tremendous things can happen. If there’s a history behind something, then grants or academia can support it. Being artists, it is hard to part ways with institutions. Sometimes we rely on them for jobs or exhibitions or funds. So I feel like it is so important to make this case. I see it as a case.

MS: I think it’s important because when things are documented and a history is paved, tremendous things can happen. If there’s a history behind something, then grants or academia can support it. Being artists, it is hard to part ways with institutions. Sometimes we rely on them for jobs or exhibitions or funds. So I feel like it is so important to make this case. I see it as a case.

MJE: It is a case. It’s totally a case. I have a curatorial project -which will hopefully come through- which will be about this topic. But because of being in Mexico where there isn’t that much of a tradition of abstract painting... The tradition is the muralists, and Frida Kahlo, and Rufino Tamayo, and figurative painters, people would come to my

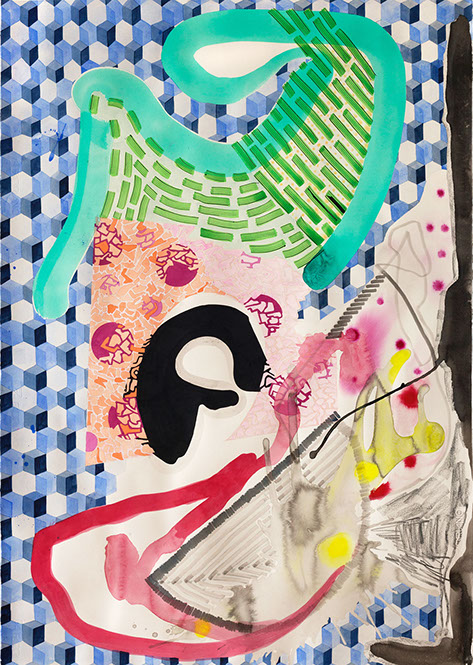

Requirements of a future tense

Mixed media on paper, 38" x 28", 2015

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

studio in Mexico and immediately say these are the gayest paintings I’ve ever seen. I’d never really thought of it in that way before. That my lineage is yes maybe Frank Stella, but also includes a lot of female identified abstract painters and queer identified artists as well. For me, it isn’t the trajectory of Jackson Pollock that resonates. That feels like it doesn’t have anything to do with me. There’s no definitive thesis. It’s just good to ask these questions about what can abstraction do and does it have to be in the work? Can it come through in the writing on the work? I think these questions are always things I’m wondering about.

MS: Let’s talk about the patterns a little bit.

MJE: You use them too.

MS: I use patterns too. And my mom’s an artist, so I grew up in a very beautiful home in the suburbs. So when I see your work, I connect to it in a deep way. I’m wondering, what does your apartment look like? (laughter)

MJE: My apartment is almost minimal actually! The only things that are really patterned in the apartment are a couple of paintings that I have on the walls. So I went for undergrad to art school and then I left and went to Environmental Design school for a year. I was making very geometric, taped paintings at the time, and they were based on interior spaces so it seemed like a natural shift. When I got to the year of design school though, everything was so rigid. I still made art during the time in design school but all the rigidity and geometry had to leave the work immediately, because I was already doing it for 8 hours during the day at school. So I had this funny relationship with shapes and what you do with shapes. I searched around for a long time about how to make abstraction, and I would make abstraction that had quotes from old dutch wood engravings and things. At some point I just kind of gave in to patterns. I don’t know how to put it. There was an art teacher I had at school as a kid whose name is Andrea Krauss -whose work is very patterned. It has fields of flat pattern that somehow interlock into a pictorial, representational thing. And I don’t know, I stop people on the street and ask if I can photograph their clothing. There’s something about design that I’m really interested in. So now I’m using a lot of patterns but unlike in earlier work, they are now all hand drawn. To draw them feels like a way of taking back this visual stuff that was at some point designed -either by hand or with a computer- and then sent out into the world, and in it’s travels became totally anonymous.

I was really fascinated for a long time -I don’t know if you’ve ever worked with these- with the security micro patterns inside of bank envelopes.

Two of hearts (I need you I need you)

Mixed media on paper, 9"x7", 2015

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

MS: Oh, those are great! I’ve always liked them but I’ve never worked with them.

MJE: I worked with them for a while and I thought this was you know… Sometimes as an artists you think “what’s my thing?” Maybe this is my thing, the guy who uses the security patterns from inside of security envelopes. And it was like no, that’s not my thing. That’s too specific. But the idea of patterns has stayed. They come from textiles, they still do sometimes come from envelopes. They come from clothing. They come from my brain. I’ve had the chance to travel so they come from different parts of the world but I’m always thinking like that. I’m always looking for patterns. I teach a lot, and if a student has amazing patterned socks, I will comment on it in the middle of a lesson. I can’t help myself.

MS: It’s like you’re making mental inventory.

MJE: Absolutely. And then I come here and it all gets transformed. I also think about the Memphis group a lot. This is an Italian group of designers that worked together in the 1980s. The most famous of them is the designer Ettore Sottsass. I think about him almost in context of Frank Stella -in a way that Frank Stella went really out of favor in the 90s and Sottsass similarly, whose stuff was so 80s, was left out.

MS: It’s mesmerizing. This book we’re discussing is Memphis research experience: Results, failures and successes of design. Rizzolli published it. It’s by Barbara Radize. Thanks Barbara! It’s an amazing book. I can totally see that now, looking at this, but what I see here is an all over pattern and you’re kind of breaking that pattern. You start with a structure and then it breaks.

MJE: Always. Yeah, I think a lot about this idea of relational painting as applied to abstraction -especially in the 60s, where if you made a black mark at the top, you had to make a black mark at the bottom, so the eye could travel out. What I’m trying to do is break that, break myself of that.

And that means breaking the patterns. That means not having a pattern that starts in one corner and trails and snakes down into the other corner. It means giving you some surface that’s fractured, so the eye goes an inch, and then has to make a left turn.

Someone I respect said to me once that my work was beautiful, but not tasteful.

MS: Why’d they have to say that? I find those types of statements funny.

MJE: But I have to love that! People have different reactions. I will often get questions like “why do you make such ugly paintings?” To me they’re beautiful. But that’s ok if someone reads them as not beautiful, because beauty is not the goal. It is interesting -people’s different perceptions or codes of what is beautiful, what is elegant, what is not.

Requirements of a future tense

Mixed media on paper, 38" x 28", 2015

photo courtesy of Mark Joshua Epstein

MS: Yeah. I just started to think about Lori Ellison‘s work.

MJE: Yeah, she just passed away. I just saw one at Underdonk Gallery. I’d never seen one in person.

MS: They’re beautiful. Kind of living in that tradition of pattern making, I would say that you definitely have a kinship. There’s a connection. She had a big show at McKenzie when it was in Chelsea. There were works on papers and then works on panel. The main difference between yours and Ellison’s would be that yours often have an explosive pattern.

MJE: I’m sad to say I didn’t know her, but because of social media -that when someone passes away their work pops up in all these different places because people are paying tribute. The drawing of hers that I saw recently at Underdonk was so beautiful. The work made me think about the idea of being what I call a table artist instead of a wall artist, that idea of sitting… I have a ten foot long work table in here, and something I’ve realized in the past two years is that I work better if I’m sitting at a table because the world disappears in the periphery. It seems like she might have been of that mindset, I wonder if her work was made in that way.

We were talking before about working in different media. I was an oil painter for a while and still, in my brain, I’m an oil painter. In Mexico City, I became more of a watercolor, ink, marker, and color pencil guy. And I know that you work in acrylic. I think there’s a kind of… I don’t know if it’s a freedom because of the history of acrylic paint is less lengthy, or if it’s just something about “this is water based”, “it doesn’t smell weird in here”, “I don’t need to wear gloves with acrylic”. Something really changed. I was originally making only small works on paper and then I started working thirty by forty (inches). There’s something really important to me about the spontaneity of working on paper. Maybe this is true of painting in general, but just being able to think it and then do it. Or don't even think it first. Just do it. And of course there’s a financial aspect in that paper is relatively cheap, and so if a painting doesn’t work out, you can get rid of it. But there is a funny market thing going on also, because works on paper are not as attractive to people as panels, or canvases are. Maybe it’s something about that weight -I don’t know why- that people are into.

It feels kind of funny though to be able to stack a year of work.

MS: It seems like a smart decision, especially if you’re traveling or you can just get a portfolio and take it with you.

MJE: I had the chance to meet Nina Bovasso last year -an artist whose work I’d admired for a long time. I like to just reach out to artists whose work I’m into, and usually people let me come over. Nina works on paper and she gave me practical tips on what paper to use and how to deal with it. Her work also deals formally with patterns and breaking patterns and thinking about that. She was incredibly generous to me. It’s really nice to be able to find those people.

MS: It’s the best.

MJE: It is the best.

Mark Joshua Epstein in studio, November 2015

photo courtesy of Melissa Staiger

Mark Joshua Epstein is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. Epstein's work has been shown in recent solo exhibitions at Brian Morris Gallery New York and Illinois State University and has upcoming shows at Biquini Wax, Mexico City, and Demo Projects in Springfield, Illinois. Epstein has participated in a number of residency programs including the Millay Colony, the Macdowell Colony and the Saltonstall Foundation.

Melissa Staiger is an artist and curator based in Brookllyn. She has a Bachelor of Fine Art from Maryland Institute, College of Art and a Master of Fine Art from Pratt Institute. Her work has been in group shows at ABC No Rio, Arts@Renaissance, The Bruce High Quality Foundation, Denise Bibro Fine Art, Heliopolis Project, The Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, The Painting Center, Sideshow Gallery, Ventana 244, and the Wilmer Jennings Gallery. Staiger teaches Abstract Painting, Color Theory and Intro to Printmaking at Trestle Gallery. She was nominated and attended the Robert Rauschenberg Artist Residency in Captiva, Florida and recently has been selected as the Curator in Residence at Trestle Projects located in Brooklyn, NY.

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.