Twitter profile picture Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, 2013

Intent and Response

Precedence

Images can be anything–mental or physical, fact or fiction, abstract or representational, and all cracks in between. The only things they cannot encompass are three-dimensional space and fourth dimensional time, though they exist within these parameters. Images, in physical form, are the primary source of how humanity traces its culture and history, from the time of the caves of Chauvet and the recently discovered Sulawesi. Since this time, our understanding and production of images has been subsequently, at times beautifully, mangled, expanded, complicated, pulled apart, desecrated, and sanctified through what we now call art, or more broadly, visual history.

Since widespread literacy, images have also been paired with the written word, usually in the form of caption or explanation, an attempt to either guide response or elicit understanding. Images, however, have significantly proliferated since certain advents of technology, printing then digital; the subsequent issues of which Walter Benjamin presaged in his 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility”. As images multiply and evolve in medium and scope, any associated text becomes both catalyst and debilitator, a framework which is torn down and rebuilt as we subconsciously follow the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words.” In order to discern intention, particularly behind art images where intention is assumed, and gauge response, we are in a constant hurdle to find out which thousand words those are.

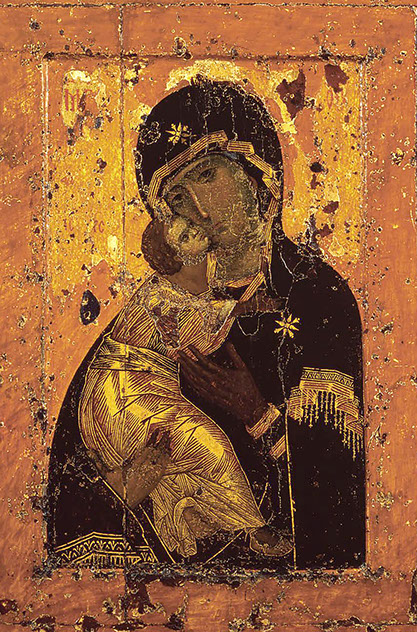

In Western art history, a precedent tradition of intention and response is Christian religious iconography. In Hans Belting’s 1994 Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, he delineates how religious icons, such as in the Byzantine tradition, were defined by who used them and how. The painters of pre-Renaissance icons were mostly anonymous in order to sustain the idea that the Holy Spirit, through the hands of a servant of God, created them; thus, subsequent images were copies of an ultimate original. A preeminent example of this type of painting is the Theotokos of Vladimir, a 12th century Byzantine icon now revered in Russian Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Theotokos translates roughly from Greek as “Birth-Giver of God”, and is an Eastern iconographic rendering of the Virgin Mary and Christ as a child, akin to a Madonna figure. This pictorial lineage of the Virgin Mary, according to Belting, is supposed to have originated with Saint Luke, for whom it was believed that the historic Mary sat in front of for her first portrait. This type of myth sanctified the iconographic tradition, setting a model for image production.

The Theotokos of Vladimir is rendered in high Eleusa style, that of tenderness between the Virgin Mary and the Christ child, of which Belting expands, “In the icon[s], [Mary’s] meditative gaze is anticipating the sorrows to come. The device of anticipation (prolepsis) produces a synopsis of two feelings and two time planes.” The Virgin Mary is nuzzling cheek-to-cheek with her child, but stares straight out towards the viewer, her eyes somber and mouth downturned. Her joy with the Christ child is tempered by her omniscient knowledge of his sacrifice and death to come.

Of course these icons were understood not as art, but as objects of faith power. The faith that coursed through these objects was cyclical, and the images became mediators, which both bestowed and reaffirmed belief. Being sacred, these images at times competed with political and religious authority, which attempted to tighten Christian theology, resulting in the infamous Byzantine iconoclasms. Yet images always proliferated, and iconographic themes became incorporated and morphed into art during the Renaissance and after the Reformation, creating the canon of Western art history.

The Multifarious Image

David Freedberg tackles the question of images and how we anticipate and react to them in his 1989 The Power of Images: Study in the History of Theory of Response. As the title promises, Freedberg urges a response-based approach to images, as a method for increased awareness of what images do, how we see them. Specifically, Freedberg opposes the rational impetus to discern intention and context, as a convolution of reading images before seeing them. He also uses the example of Theotokos of Vladimir, to illustrate the potential of arousal by image, through an anecdote of a young Arshile Gorky’s action of passionately kissing the Theotokos,

Gorky was impelled to kiss the picture of the Virgin in the way he did because he had been conditioned to view women in a certain way, and especially women regarded as beautiful. But what is central in the whole actions is that he could only thus be moved if he perceived that particular image of Our Lady of Vladimir as a particular mortal (and not as the Virgin generalized by the picture); and so he responded to it as if it were living, and inclined to whatever passions–including sexual ones–that living forms normally induce.

Theotokos of Vladimir

Tempera on panel, 104 x 69 cm

1130

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

This is not the only example of someone being so moved by art they were compelled to kiss it, as if it were a loved one who could return the affection. In 2007 in Avignon, France, the artist Rindy Sam was arrested after she kissed one panel of Cy Twombly’s abstract painting triptych Three Dialogues (Phaedrus) (1977). The triptych consists of two 9 foot by 6 foot panels, offset by a smaller, framed print. One of the panels has a forceful scrawl of red oil stick, while the one Sam had kissed had been all white, leaving a smudge of red lipstick–perhaps a gesture for symbolic balance. Sam defended her action, “I just gave it a kiss…it was an act of love…I was not thinking.” Cherry-picked as these examples are, they are evidence that images can be sensual, and hold more power of the viewer than could be predicted or captioned.

Perhaps this power of images is what Benjamin is circling in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility,” with his concept of aura, as a way to associate time and space with authenticity of an image, and subsequent sensation in the viewer. Yet, it can’t be that simple, as Benjamin himself complicates, “The definition of aura is a unique manifestation of something remote, no matter how close it may be.” In this way aura can be approached anachronistically via the Theotokos of Vladimir and the concept of prolepsis, as an imposition, and almost synthesis, of one feeling and time plane onto another.

Benjamin argues that in art before mechanical reproduction (including intaglio and etching techniques, as they still involved the inaccuracy of the manual), works of art were necessarily bonded with ritual, as in religious iconography, which would establish aura and guide response. Looking at Theotokos, devotees will understand through presentation and context of church authority and dogma how to respond to this and other singular images. With increased accuracy of reproducibility, ritual has shifted to modes of reproduction, and aura is veiled by multiplicity of the image. This is not to negate the power in images, as previously discussed. Rather, the power and aura of images, in their multifarious lives through reproduction, becomes harder to pinpoint and name. Our response, if not something as visceral as a kiss, becomes ever more dependent on the words that contextualize and frame images, which can now be viewed across space and time.

Selfie as Effigy

The front page of the May 5, 2013 issue of the New York Times features a self-taken photograph of the “Boston Bomber,” Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The image, retrieved from Tsarnaev’s Twitter page, looks like a typical teenage “selfie” –a portrait from the chest up, his upper arms tense forward, indicating he is holding the camera, presumably a smart phone. The light source from the top right bathes his baby-face and tousled hair in a warm glow. There is a hint of burgeoning masculinity in a faint mustache, goatee, and flexed pectorals. Also present is a half-hearted smile that reaches his eyes.

Tsarnaev and his brother, Tamerlan, had a month prior, on April 15, set off two home-made explosives near the finish line of the annual Boston Marathon –killing 3 and injuring an estimated 264 others. Tamerlan was killed in a subsequent firefight with police on April 18th, while the hunt for Dzhokhar shut down the city of Boston until a day later he was found, injured, hiding in a boat in a resident’s backyard. As this is being written he sits in custody, has plead not guilty to 30 charges, including murder, and awaits a November 3rd trial in federal court.

A month after the New York Times printed Dzhokhar’s selfie, Rolling Stone ran a cropped version of the same image on the cover of it’s preemptive August 3rd issue. The choice generated a fiery backlash, particularly in New England. Oft-quoted was then Boston Mayor Menino who, in a public letter to Stone editor, Jann Wenner, concluded, “The survivors of the Boston attacks deserve Rolling Stone cover stories, though I no longer feel that Rolling Stone deserves them.”

The New York Times cover received no such backlash. Perhaps the discrepancy had to do with timing; the public’s shock and grief had turned to anger and a desire for justice, even revenge. The gulf in expectation between the New York Times and Rolling Stone sets up this diachronic response; a newspaper front page is supposed to indicate serious journalism, whereas a glossy, large-form magazine cover suggests at best a gilded interview, at worst a soppy exposé. In his letter, Menino opened with, “Your August 3rd cover rewards a terrorist with celebrity treatment.” Most importantly, it may be that because the image of Dzhokhar in his vanity had already been seen and digested in the public realm (the television media had used the image when reporting Tsarnaev’s back story), the repetition on a popular culture magazine’s cover felt like salt in the wound, a dig at how Boston could be brought its knees by a boy who looks like the fourth Jonas brother.

The story of Tsarnaev’s selfie underscores the importance of an image’s frame and trajectory. To make an unruly comparison, the formalism in the self-portrait of Tsarnaev is not unlike those of religious icons, context excluded. Tsarnaev is pictured as a singular figure from the chest up, surrounded by an angelic glow; his eyes seem to plead for empathy or belief. Filled with conventional signs of innocence and charm, Tsarnaev’s intent with this self-portrait can be assumed to be simply a young man attempting to present himself as attractive. And it’s not what we want to see. Is the image wrong? Are we wrong when, looking at the image, we want some hint at a possible motive, a clue to Tsarnaev’s alleged intention to destroy human life? This disjunction is compounded by the image repeated instance on multiple broadcasts in various media, accompanied by extensive descriptions of the terror he and his brother allegedly committed.

The media’s intention is flexible and impossible to assume with precision. Historically, though, images have been, and to an extent still are, defined by their use. Religious iconography is imbued with faith, therefore enacts faith. Yet with the reproducibility of images, there is no longer a direct 1-1 correlation between intention and response. Images are layered as much as we are.

Traces of Reality

Images of evil, of those who do evil things, further rupture the correlation between where images come from and how they are received. Hannah Arendt, in her Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, diagnosed this disjunction of how evil comes into being and what that looks like,

Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man [Eichmann] was not a ‘monster,’ but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown. And this suspicion would have been fatal to the entire enterprise [his trial], and was also rather hard to sustain in view of the sufferings his like had caused to millions of people, his [Eichmann’s] worst clowneries were hardly noticed and almost never reported.

Here I think of Tsarnaev, although there is an obvious gulf of difference in situation and time. What if our accumulated behaviors don’t align? While this prospect of an evolving, undefinable self is potentially liberating, it is also a horrifying fact of reality –understanding that evil is not placed upon us, but rather grows within and alongside us.

What is truly upsetting about the Tsarnaev photograph is that it is both utterly correct and wrong: a self-portrait of a young man looking for likes on Facebook and a haunting identification of a terrorist, who allegedly committed senseless murder. This is particularly important for not only understanding who Tsarnaev is, or how terrorists are born, but for the approaching photographic images in general. They can never be accurate or succinct, as artificial snapshots of time. There is an illusion that they are information by having information surrounding and demarcating them, essentially captions. A more precise approach would be to understand photographic images and their surrounding identifiers as regurgitated traces of reality, rather than reality itself.

With his upcoming trial, we will undoubtedly see images of Tsarnaev in courts, facing what we hope to be justice. Critically, one must realize that these types of images, of news, of the world and war, are not spontaneous. Each photographic image published has several intents and purposes behind it, and will ripple outwards toward multiple sites of reception. This sociological given is compounded when considering what images are, in their ability for prolepsis, to multiply reality. To attempt an almost literal balance, equal self-reflection and critical reading are required. There should be consideration of how images are made, distributed, understood, and most importantly, used–lest we fall headfirst into the digital deluge of media.

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.