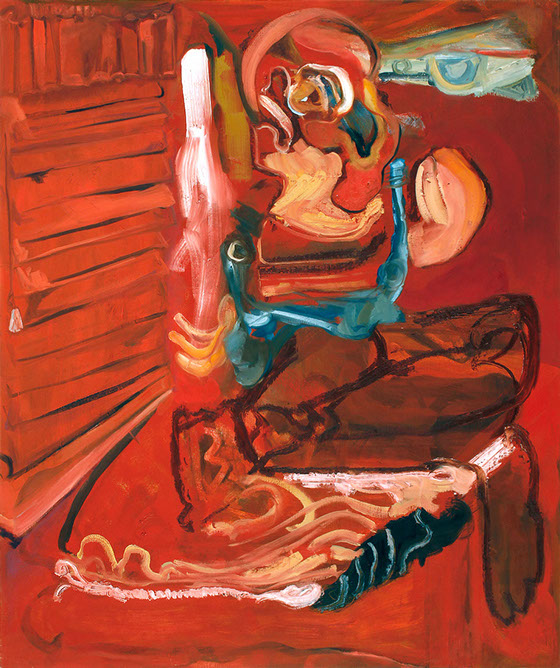

Field Day, 2014

Oil on canvas, 40 x 32 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

Eric Sutphin with Ashley Garrett

Eric Sutphin: You’ve done a number of interviews with other painters. How did those conversations come about?

Ashley Garrett: I’m interested in other painters’ processes. I like to talk with artists whose work gets under my skin in some way –looking at their work usually brings up particular questions that I’d like to ask them. I’m curious to know how their work develops, how it changes, what questions they are asking themselves. With Lisa Sanditz I wanted to know more about her series of paintings based on Chinese factories and industries –the whole question of being an outsider in another culture; how does she address that? I really wanted to ask her about that and about working with narrative in painting. Most of these artists are very open about their processes and their thinking, how they’ve come to a resolution. I think that’s a really interesting process to peek into.

ES: I have the sense, in looking at the cross section of painters that you've talked to, that you might have been responding aesthetically to what they’re doing and that by having a conversation with them, you could get more insight into what they are doing in their studios.

AG: Yes, and also the history of how they each arrived where they are now, how they got to where they are in their work. I’m interested in talking with a range of artists from the representational to the completely abstract. Lisa works with narrative, figuration, imagery, representational forms, while Joanne Greenbaum is doing something completely different. She’s very much concerned with invention in her mark-making and opening up different forms as she works, both with line and color. I thought it was so refreshing to have this celebrated artist say so directly “do whatever you want, don't let anyone tell you otherwise, just keep painting.” And I love that, going to very different methods of working and seeing what these artists have to say.

ES: On my way here I was thinking about two generalizations of painting right now. The “zombie formalism” thing and the “abstract/figurative” thing. So much of what I see falls into those categories. But I think that those binaries get set up in part because of criticism, and partly because styles get assigned. So what we see in galleries and museums, we have to file away into these categories. It’s dangerous in a way because then we stop seeing what’s actually there.

AG: So why not let these painters have a chance to break that down?

ES: There was a part in the Greenbaum interview when she was discussing the idea of mapping. She said that that hadn’t been her intention but because ‘mapping’ had become a buzzy sort of term or idea in painting, that’s what everyone saw in relation to her work. That is one example where the art stops speaking for itself and the discourse-at-large starts to take over. Right now, there are many

Ashley Garrett in studio

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

painters who are invested in what people like to call ambivalence, or straddling, or “being multiple things at one time.” I’m thinking of a painter like Michael Berryhill. Having it both ways, or many ways, is one way painters are trying to eschew these simplistic categories. I see that in your work too. At times, there’s something “of the world” to latch on to but as soon as we can attach to the figure or the form we slip away into the painting. We’re in a continual state of transformation. It seems to me now, with so much contemporary painting, that there is very little of the concrete, the fully formed, that this kind of painting speaks to a present sort of schizophrenic consciousness, skipping around between so many things.

AG: I’m trying to include all of the possibilities of perception at once. I was just looking at that part of the Plato Dialogues –the conversation between Socrates and Theatetus about knowing and not knowing, showing how fluid all of this stuff is. How can the mind contain all of these contradictions at once? You can’t possibly know if you don’t already know. There are all of these parallel ways of thinking and knowing, mistaking and perceiving. So how do you work from a place where you have a memory, but are in the process of forgetting it as you go? Or not having fully remembered all of the details in the first place, and working within that place? I think that even a couple years ago, straddling the line between abstraction and figuration was more “of the moment,” and now people are looking for other things.

Slater, 2013

Oil on canvas, 38 x 32 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

ES: Absolutely. We’ve hit a point of saturation, it entered squarely into the discourse but now it seems stale.

AG: I wonder if at least some part of it is an anxiety or fear of working. Artists can be, as you're saying, schizophrenic, but it’s not just in the work, it’s also in the world. The pressure to get something down and publicize it can be pretty intense.

ES: Well that’s something that has been frustrating. Sharon Butler uses the term “self- amused, but not unserious painters” and that phrase keeps churning in my mind. I’ve been looking at a lot of contemporary painting shows very recently, in particular the show up now at Gavin Brown (Call and Response), a big salon-style group show, and there is so much self-amusement. It’s solipsistic because it becomes a string of one-liners and inside jokes, maybe a quick little sketch that relates to a meme or to something in pop culture, and there’s a giggle factor. But there is no sustained rigor or investment. And you know, plenty of people will argue that those are old fashioned ideals…

AG: I don't think so. I’ve been told this by so many artists and I love it –people will always be writing new novels, theatre, great music… I mean Bob Dylan is still making music! There’s plenty of room for all kinds of painting!

ES: Absolutely. Genuine work, work ethic... An ethics in the work is not something I think is bound to taste or fashion. It’s persistent and its presence will always show.

AG: I’m very much a supporter of sustained, thoughtful working and pushing things as far as possible, and how that allows the work to really develop. The other thing is that very few artists will actually identify themselves as “casualists.” They think, “I’m not casual, this isn't messing around, this is serious!”

ES: But throughout history there is often a disjunction between the terms assigned to “movements” and the practitioners. Cubism, for example. No one wanted to be a cubist but the term stuck. So the nomenclature is a part of the critical apparatus, the need to coin the term. I tried to get to that idea in my essay “Roelstrate Response” that not only is it a fear of actual sustained work but that it’s impossible for many people, with the demands of debt, multiple jobs and balancing all of these aspects… it reflects in our cultural output. But there’s room for it all. I think there has been a turn recently toward figurative work, have you noticed that?

AG: Yes, I have noticed that. It’s refreshing! And a turn towards narrative in painting. It’s becoming okay to work with that again too.

People often ask me in studio visits whether or not I’m painting from life and I always say no. But over the holiday I thought that I’d like to try doing that, it would be an interesting challenge for me. So I took some things that I was personally attached to and painted them. These are still lives from Christmas ornaments that I made as a kid, all 10 x 8 inches, oil on canvas. They're very funny things, made out of tin cans, tinsel, Styrofoam, pipe cleaner, yarn, buttons - little kid craft materials. When I was little my mom was really invested in the creating a beautiful, enveloping Christmas experience but as we got older she decided that everyone was over it and that made me really sad. So whenever I look at these ornaments I think about that early experience of Christmas magic that I had that was kind of limited, I haven’t really had that as an adult. I thought I could take these, which are some of the most personal, meaningful objects I

Ashley on New Year's Eve '90, 2014

Oil on canvas, 10 x 8 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

have, and paint them and see what I get. They also have school photos on them. The shapes are weird, you can see the marker lines, they're so quirky and sweet.

ES: So you made these paintings upstate?

AG: Yes, in the small living room studio my husband Brian Wood and I share. So the small painting size really works for that.

ES: I was thinking that the physical space that a painter is working in directly affects what they're doing, whether you have an attached studio or a separate studio, so obviously that shaped the scale you were working. Also your proximity to your subject…

AG: I talk about this with other painters a lot. Even in my current studio, it took me a long time to figure that out. It took me a while to get into a routine where things were set up right, for a while I was fighting against my own set up. I didn't even know, but it affects the work so intensely and really specifically. That’s also part of an artist’s development—figuring out what kind of studio they need. So I was painting these “ornament paintings” in a really small space and the set up was pretty physically tight, and there was all of this material around. And looking at these now, I’m thinking that I don't know if I could have made these here in the city. I usually like this mid-sized canvas –in the 30 to 40 inch range. It’s a really interesting thing to shift between scales, and the scale of your own workspace. I only used to work very large and with palette knives. I’m gradually getting back up to scale. But it’s taken me a while to adjust to brushes.

Crest, 2014

Oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

ES: It’s a completely different sort of tactility, brushes versus knives. In a way, a brush requires more control. This makes me think of Guston too. He jumped around wildly in scale and between media. Later on, he was making these little drawings of “artists things;” a shoe, a stretcher bar. It was his way of zeroing in on a kind of vocabulary that then anticipated the late work.

AG: Right, and I don't usually work in series like this. It’s not a sequence exactly but it is a group. They start from ’88 up to ’92, year by year. For me to work like this was really interesting, painting from an object and then there’s the sequence. They're completely self-contained; each has its own intrinsic logic.

ES: How did you arrive at the space that the objects are occupying?

AG: I had a group of paintings that I had painted from a long time ago. So I would start with a base of some kind, some of them were barely there, some were more resolved, so I was painting into that space and then looking at the still life setup. I put the ornaments in a tiny box that I hung with different colored fabrics. The little angel painting, for example, there was a striped shirt behind it, I wanted to get some of that spatial quality, and a lot of the green was already on the canvas. So I was responding to what was already there on the canvas and what was in front of me. Looking for the image and the figure in the space. There was also a lot of glitter on a few the ornaments, and you know, everybody loves glitter now, but I thought I’m not going there!

ES: In a way it’s very funny to use these brush marks as stand-ins for glitter. It’s “anti-glitter”. They end up being these clunky dots. There’s just no way to make it look like glitter unless you're Rembrandt. But I think that adds a certain charm that was in the original ornament.

AG: It’s more about the mark, the wet-on wet technique. It’s nice that the objects have a life outside of their original context, and I thought that adding actual glitter to the paintings would interfere with that.

ES: It’s a continuation of a personal history, not only of a life history but also a making history; these were among the first things you ever made.

Weona, 2015

Oil on canvas 42 x 37.5 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

AG: I wanted to have sort of a dialogue with the little kid Ashley that made this. “Lets make it again!”

ES: It’s a way to honor that little you, you’re thinking; “I’m going to sit here and look at you, ornament, for hours and recreate you and think about who made you.”

AG: Right! And some painters that I’ve interviewed do have that kind of a relationship with their own work over time. They end up making a dialogue between their current selves and their earlier work. Maybe I’m not old enough for that yet, but I thought that I’d like to use these because I did make them a long time ago. I don’t reminder making them but looking at them like this was like rediscovering them. I felt that I had never seen them before, but I knew exactly what they looked like.

ES: It’s creating a different context for the objects. There’s a history attached to them, then you take them out of that, they're displaced and then you put them back into it. When they were made, you didn't know who (Philip) Guston was. All of these influences weren't there. So in that very simple way, they become integrated in a bigger history. That’s another thing I was thinking about. In some of your older work, there are images of say, a bureau or a piece of furniture, and it made me realize that when artists are painting interiors or maybe even still lives, there’s a kind of voyeuristic urge from the viewer, like “am I going to know something about the artist because they are showing me their stuff.” I guess that’s maybe something I respond to with figurative work, when an artist takes things from their material life, the things that surround them.

AG: This has come up in other situations, where people have wanted to hear the backstory of these paintings. I have to figure out when to tell and when not to tell. That’s always a difficult thing. There are a few people who don't want the whole backstory. They want to see what they see and not hear what’s behind it. I enjoy telling the stories. Its fun for me. All of these paintings have very different, specific reasons for being here.

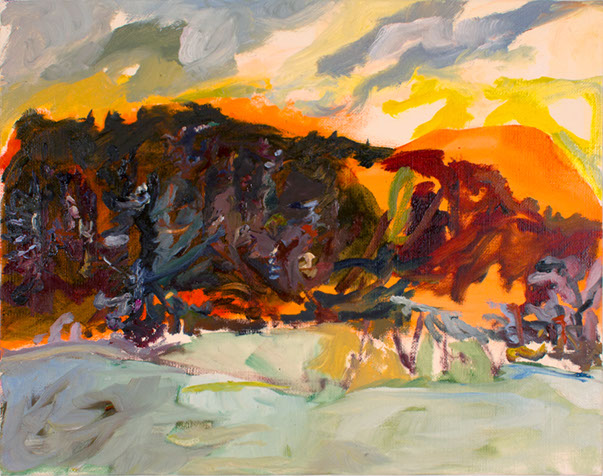

Red Rock Late Afternoon, 2014

Oil on canvas 11 x 14 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

ES: I’m more a person who is inclined not to want to know. For example, I see a thing, but I don't know what it is. It’s specific, but the associations never end, it continually changes. That for me is the site of the pleasure. The guessing game of what it might be. But there’s also the paint. I can see the paint, and go back and forth. I think, “maybe the paint will tell me something.” But the paint is just paint. If you tell me, “oh that’s a trumpet” that’s the end of the game.

AG: Well you're on the right track… and this is different than the whole “abstraction/figuration” idea, because even when the objects are in an environment, they are grounded. They're actual things. There’s earth, heaviness, weight. These objects are not “barely there” they’re not coming and going in terms of being “barely suggested.” That’s the important thing in this work.

ES: In all of this work there is a high level of specificity. I know that it’s yours. I know you have seen it. A lot of current painters enjoy the “quick suggestion” of a person, a text or something and it doesn't feel specific or invested in a personal history. It just feels like an empty sign, like “let me show you this thing that I know about.” That’s not what your work does. These objects are integrated in you to the extent that you are able to present them as being both general and relatable. They register as belonging to you but also belonging to the world.

AG: I know these places really well. It’s weird how these things emerge. Sometimes a thought is bothering me and I have to work with it because I keep thinking about it. Occasionally an idea for a painting is triggered by a smell. Or, I remember how gross or rusty something was. Especially things I no longer have access to. The objects are themselves but they're also loaded with emotional attachment and association. How does the object soak that up?

ES: Even though these are resolved, all of the objects seem soft, or maybe heavy. These trees are sagging. And this instrument form, it feels banged up. Every object feels weathered. It seems more metaphysical than actual. These images have been clanging around in your head for a while and they’ve accumulated this wear and tear. There’s a heaviness present in them.

AG: Yes, I think that’s a really good way of describing the paintings and the process. When I was coming back to painting around 2011 I was doing a lot of drawing. Drawing from life, drawing trees and landscapes. This past summer I saw that Sarah

Red Rock Moon, 2014

Oil on canvas 11 x 14 in.

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

Hollars was doing plein air painting. She was in Oregon in the summer and painted from life – all kinds of things, landscapes, mountains, skies, her dog, a llama. And I thought they looked so fresh and beautiful. I really wanted to try doing that and again adding the challenge of looking at something real, so I started this fall and winter, right around Thanksgiving when there was an early snow upstate. The winter light is incredible! It’s really difficult, the paint freezes! It was fun because I found myself doing the opposite of what I had always told people I was doing. I mean, in studio visits people ask me “don’t you ever paint from life, don't you use still life?” So I thought I’d do exactly both of those right around the lost magic of the holiday season, and being upstate adds a certain kind of clarity. When you really start looking, you realize how much there is to see! The landscape changes so fast.

ES: I think plein air painting gets a bad rap because it gets associated with a certain impressionistic aesthetic. But then I think of Charles Burchfield or Lois Dodd…. or even Mondrian. It all came directly form nature. It looks like all of these paintings are painted from the same viewpoint, are you standing in the same spot?

AG: Close; the angles are slightly different. Where I grew up in Pennsylvania there were small mountains/large hills and tree lines and I always thought they were interesting formally. How does everything fit together? Where do these trees sit in space? They appear like they are on a flat plane, but they’re not, these really dense forms look as if they’re hanging in space. I really wanted to work with that. Plein air seems like a really uncool thing, who does that? So why not? There’s so much pop reference now that I just wanted to go really far in the other direction and see what comes up out of it.

ES: It seems to me that a lot of the painters using irony or doing the “zombie” thing, “pure surface” stuff. These people are our peers –we’re all drawing from more or less similar references and resources. But you seem to be examining the present in another way, showing that there is an alternative. Some of these other contemporary painters, it seems to me, can’t divorce themselves form their own personality fast enough. But that’s not what you're doing –you are eager to put yourself into these paintings.

AG: I want to be vulnerable in the work in some way. I mean, look at Guston or Morandi! You can really feel them in their work. The form and the emotional content is incredibly specific. There’s a great deal of personal risk.

ES: I think a sign of a great painter is the degree to which they are present in their work. They are more themselves in their work than they might be in their lives. They actualize themselves in their paintings.

Limelight, 2014

Oil on canvas, 10 x 8 inches

Photo: courtesy Ashley Garrett

Ashley Garrett lives and works in Brooklyn. Her recent shows include

Slater, (a solo show) at Chase Gallery, West Hartford, CT, Image Makers at Novella Gallery, NY, and Home Turf at Brian Morris Gallery, NY. She is also a contributor to Figure/Ground, Whitehot Magazine, and Painting is Dead.

Ashley Garrett

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.